Whale watching boats still disturbing endangered killer whales despite efforts

FRIDAY HARBOR, Wash. -- Southern resident orca numbers are the lowest they've been in more than three decades.

But you'd never know it by the bustling port of Friday Harbor on a bright September day.

Bold white letters on red signs say it everywhere: Whale Watching. Tours depart multiple times daily, taking literal boatloads of tourists from places like New Jersey and Texas out to see the majestic plumes of humpbacks and orcas.

It's not just Friday Harbor. The whale watch industry brings in roughly $60 million annually to the region's economy. Boats with the Pacific Whale Watching Association, a trans-boundary trade group made up of 32 whale watching and ecotourism companies, launch daily from 19 locations in Washington and British Columbia. The group has roughly 100 vessels.

Some whale watching organizations guarantee a sighting. And each day, smiling tourists come back to port telling tales of whale fins and soaring marine mammals.

But does it come at a cost?

With the southern residents starving, people are pointing fingers at the whale watching industry.

The constant presence of vessels disrupts the whales' foraging; their clicks muted by motors.

Leaders of the local industry say they are not the problem for these endangered whales.

Yet even some whale watchers admit: They play a part.

Above and beyond?

Jeff Friedman, the president of the PWWA, says their fleet is large, but don't let the numbers fool you. The Puget Sound is big, and they don't pester the whales with a never-ending onslaught, he said.

"I want to be clear, there aren't 100 boats on a group of whales on a daily basis," Friedman said. "Everybody is spread out."

Friedman and others argue the PWWA has voluntarily instituted some of the strictest policies in the area for boating near whales. Under its own guidelines, the PWWA requires captains to travel no faster than 7 knots within one kilometer of whales.

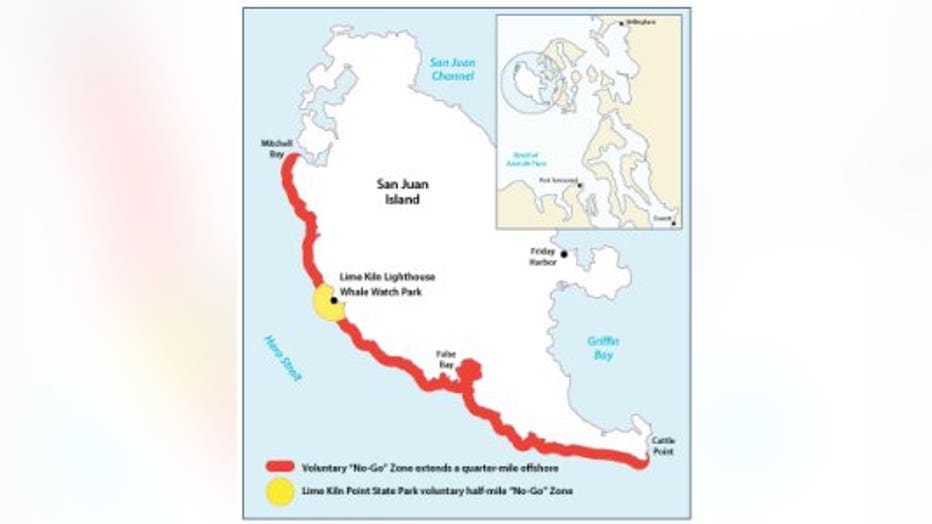

They've made bounds to protect the whales, Friedman said. Years ago, the trade group maintained a strict opposition to a mandatory no-go zone

File Photo of Voluntary No Go Zone

on the west side of San Juan Island. Now, the group's own guidelines require captains to honor the voluntary boundary.

And recently, the association has mandated captains slow their speeds. There are also time limits placed on watching one group of whales.

"We're actively working on reducing the number of boats on one group of whales," Friedman said. "We have that in our guidelines."

Of course, they don't just focus on the endangered southern resident orcas. They search for humpbacks and transient orcas -- which are thriving.

And now, the organization is considering working with the state and scientists to design a permit program. Friedman envisions a program where every active vessel gets grandfathered in, but it would limit the number of boats that can watch a group of southern residents at any given time.

All in an effort to help, Friedman says.

From KCPQ

But still not enough?

With 74 southern resident orcas left, some in the governor's task force are considering whether the PWWA should stop watching them altogether. Friedman won't go that far, saying he would speak out against a formal moratorium.

Of course, the numbers don't lie. Data from Soundwatch, a group that monitors vessel activity that could potentially harm the whales, shows changes in killer whale behavior around boats.

In 2017, Soundwatch data showed eco-tours averaged about seven boats per group of killer whales. On average, the whales are watched more 12 hours a day in the summer.

On one of the busiest summer days this year, 36 whale watching boats were counted focusing on a single group of whales, according to Soundwatch.

Not all whale watchers are happy with the progress PWWA has made. Hobbes Buchanan has piloted whale watch tours for 17 years. He quit the PWWA in 2017, after eight years with the association.

"Years ago it was fun when there was almost 90 whales and 10 or 15 boats," Buchanan said. "Now there's 75 whales and over 100 boats watching the whales."

Buchanan only pilots one tour a day, he said, compared to other companies that do two or three trips. All that exposure to boats changes the whales' attitudes, Buchanan and Soundwatch said. They swim closer together and speed up.

The whales also spend less time foraging and more time on the surface, which means they're expending more energy than they're takin in.

Even with boats 200 to 400 yards away, one study suggests killer whales' ability to detect its prey drops by 38 to 90 percent. Speeding boats - boats faster than 7 knots - further prohibit whales' foraging.

The killer whales' clicks - which they use to find prey and talk to each other - are louder and longer when the vessel noise is high.

Changes coming?

More changes - voluntary and mandatory - could be coming. Earlier this month, Q13 News obtained documents containing potential recommendations that could come out of Governor Jay Inslee's task force to save southern resident orcas. In it, there are a few recommendations on whaling watching boats.

The language is vague, but the proposal would "dramatically reduce" the number of whale watching boats around the southern residents.

Buchanan said the PWWA's latest guidelines have helped the whales. But more needs to be done before he considers rejoining the group.

"I don't think we need to watch them 10 hours a day, 7 days a week," Buchanan said. "Maybe six hours a day, maybe a day off here and there."

The task force's recommendations will be released Monday.

A late summer day the docks of Friday Harbor are sure to be bustling.