El Nino could mean a drier, warmer winter ahead for Pacific Northwest

SEATTLE -- "Sometimes what happens in the tropics doesn't stay in the tropics," says Q13 Chief Meteorologist Walter Kelley. That couldn't be more true than when we're talking about El Nino and La Nina weather patterns.

The National Weather Service's Climate Prediction Center is now forecasting a 65 percent chance El Nino conditions will be in place by the fall, and up to a 70 percent chance by winter.

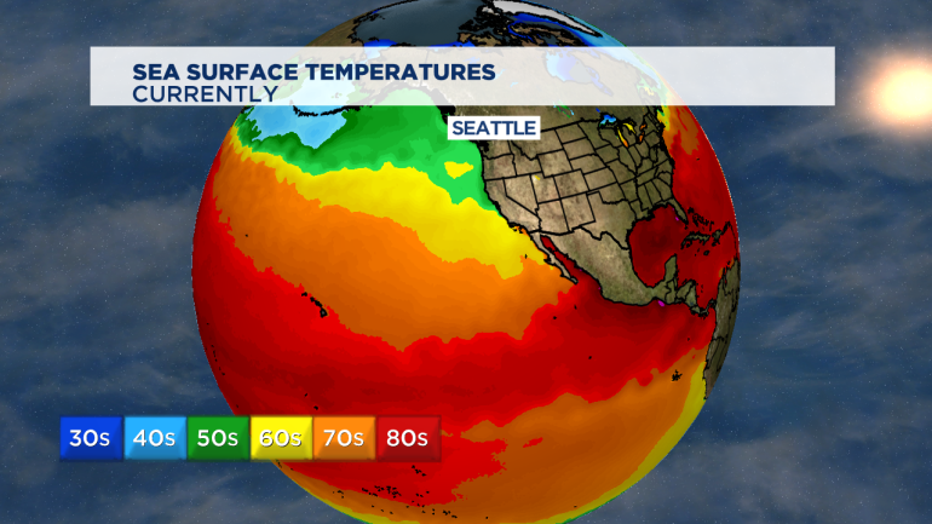

El Nino and La Nina weather patterns are the opposite side of the same coin. Both have to do with ocean surface temperatures in the tropical part of the Pacific Ocean that straddles the equator.

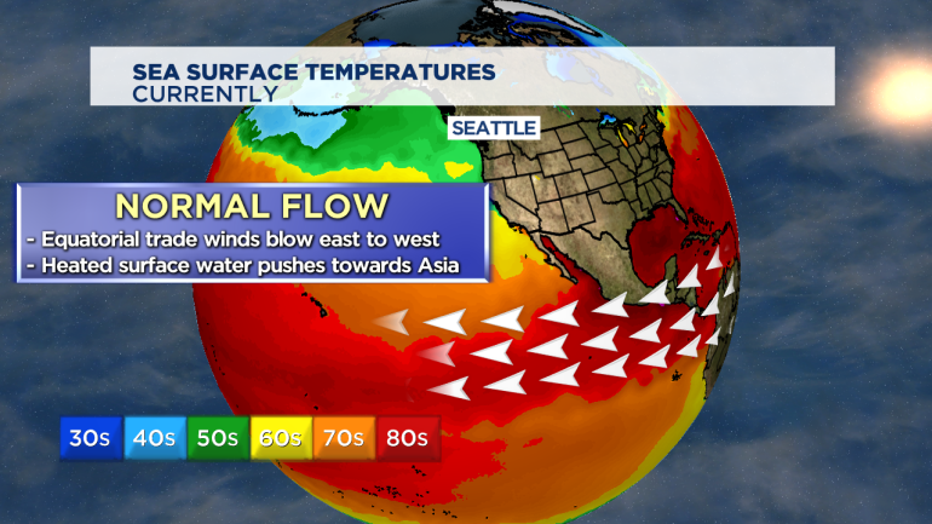

The normal flow in the atmosphere near the equator have trade winds that blow from east to west. That's the opposite of up north where we live in what's called the "mid-latitudes". With this typical weather pattern, the warmest water that's near the surface gets pushed off to the west towards Australia and Asia.

That makes that part of the Pacific Ocean more stormy with hurricanes (called typhoons in that part of the world) and drives a lot of soaking monsoon rains in Southeast Asia. This is a natural weather pattern that happens every 2 to 7 years.

When these trade weaken considerably -- and scientists don't know yet what triggers that to happen -- the heated water doesn't move away. Instead, it pools along the western coasts of Central and South America. That change in how the ocean circulates heat means it changes how much heat and water vapor gets released into the atmosphere -- and alters weather patterns around the planet. The Pacific Northwest is no exception, though the greatest impacts on average from El Nino are felt in the winter months.

In a normal winter here in the Pacific Northwest, the polar jet stream is quite variable. It moves north, it dives south sometimes. It brings in some storms. Some of them have some low-elevation snow, mostly it's pretty wet. But with El Nino, the jet stream and associated storminess generally stays well to our south. "For us city folk," says Walter Kelley, "we still see stormy days -- but less of them."

And during El Nino seasons -- it's the southern tier of states from California to the Carolinas that end up seeing the more severe type weather. That often means mudslides and flooding to the typically drought-stricken Golden State. But, since each El Nino is a tad different, this far out knowing that an El Nino pattern is setting up just gives us a general picture of what this coming winter will look like. We could still see a decent ski season and we could still have a random low-elevation snow event to hit Puget Sound. An El Nino winter is generally just drier and warmer than normal.