Hood Canal Bridge 'fix' for fish kills now being tested

Hood Canal Bridge 'fix' for fish kills now being tested

As juvenile salmon swim toward the Hood Canal Bridge, they come upon floating pontoons. Since the fish don’t go deep enough to swim underneath of the structure, they’ll naturally follow the pontoon looking for a break but due to the shape of the pontoons, they meet a 90-degree angle – which look like a wall – causing them to turn around and start all over again.

POULSBO, Wash. - It is a story scientists know well: a man-made project, accidentally creates environmental impacts no one expected.

When the Hood Canal bridge opened in 1961, it was a first-of-its kind success. It may have been the second concrete floating bridge in Washington state, but it was also the first-ever built on a tidal waterway.

The feat remains impressive to this day, not to mention useful, given its daily use connecting the Olympic and Kitsap peninsulas. However, while traffic flows above, salmon are blocked below.

When juvenile salmon begin their migration out to sea, they remain close to the surface, typically within three feet.

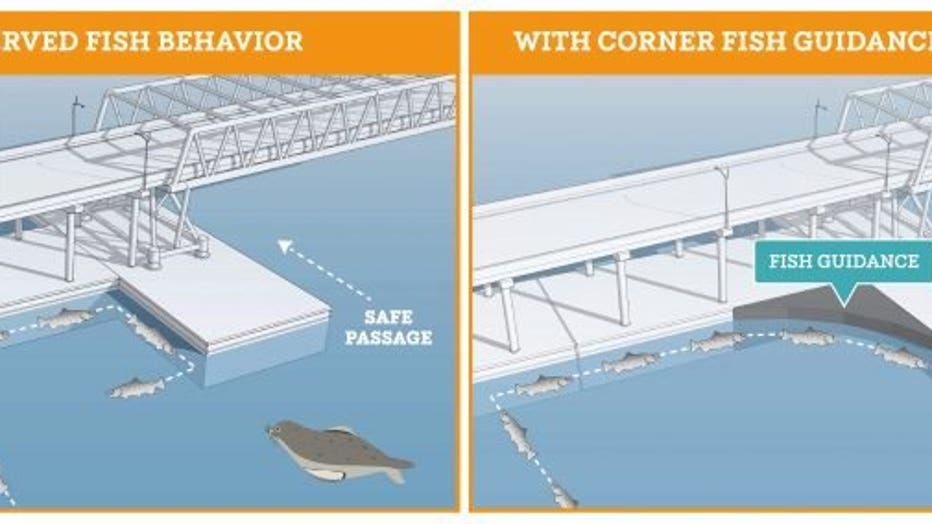

As juvenile salmon swim toward the Hood Canal Bridge, they come upon floating pontoons. Since the fish don’t go deep enough to swim underneath the structure, they’ll naturally follow the pontoon looking for a break but due to the shape of the pontoons, they meet a 90-degree angle – which looks like a wall – causing them to turn around and start all over again.

This Long Live the Kings diagram shows the sharp corners on the bridge’s floating pylons, where migrating juvenile steelhead can become stuck and easy targets for predators. The second panel shows how a fish guidance structure may help redirect the f

"It’s like a treadmill," explained Hans Daubenberger, a senior research biologist with the Port Gamble S’Klallam Tribe. "They’re just circulating back and forth along the bridge, and it’s a lot easier for them to be eaten the longer they stay there."

Predators like harbor seals can kill juvenile salmon with increased speed thanks to blockages like that.

According to research done by both the Port Gamble S’Klallam Tribe and NOAA, up to 50% of juvenile steelhead that make it to the bridge do not survive past it. That’s a remarkably high mortality rate given that only 20% of salmon that make it to the Pacific Ocean survive long enough to return.

Steelhead salmon are just one part of the problem. Chinook, chum and steelhead salmon are all listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act. All three species pass through the Hood Canal Bridge in order to make it to the ocean where salmon mature for years before returning to their native rivers and streams to spawn and start the cycle over again.

"Things like this are sort of unique," said Daubenberger. "It’s such a huge mortality at a single location with the potential for a real solution."

The solution long-term would be a new bridge. Plans for such a mega structure would take years and tens of millions of dollars. In the meantime, the nonprofit Long Live the Kings (LLTK) is working toward fixes that can ensure salmon don’t disappear in the meantime.

The biggest change is a new 70,000-pound fillet, or a fish guidance system.

The large triangular-shaped structure of sheeting and pipes was carried by a tugboat out to the bridge earlier this year and inserted into a particular location where fish tend to be turned around. It eliminates the sharp corners on the bridge’s floating pontoons/pylons that scientists hope will give juvenile salmon a better chance to redirect around the structure rather than cycle back-and-forth.

This spring, LLTK partners at NOAA and Port Gamble S’Klallam Tribe will monitor both juvenile steelhead and salmon migration around the bridge during deployment to compare to data from previous years.

In early April, Congressman Derek Kilmer boarded a tribal research vessel alongside FOX 13 to get an up-close look at the new filet.

Daubenberger was behind the wheel, as we approached the bridge – he pulled up videos that displayed how fish traveling back and forth would be corralled by seals that could turn the salmon into a virtual buffet.

"I think it’s important to put an eye on both potential problems and solutions," said Rep. Kilmer. "When you see a video of a seal corralling salmon into the corner of the bridge it’s pretty compelling. Being able to put eyes on how scientists are solving that it’s helpful to see that up-close and in-person."

The first fillet structure cost roughly $1.6 million to build. According to LLTK, future fillets should cost a little less.

The legislature recently appropriated $3.6 million to the project, though more money will be needed. Hence, why Kilmer’s interest is so important.

"This is not just a Washington state problem," he said, referencing the work NOAA has done. "The federal government should be a partner in this, and solving thing shouldn’t just fall on the backs of taxpayers of Washington so we’re going to fight for more funding to hopefully get this solved."