Is the 'Big One' coming? The science behind the recent earthquake swarms

BREMERTON, Wash. -- From the salon to the diner, the swarm of more than 50 small earthquakes this spring is the talk of the town in Bremerton.

"Kind of did one of these," says Don Ward, making wave motions with his hands behind the counter of Timothy Stamack Salon in downtown. "I was like 'what's that' and my mounted televisions wobbled."

Ward is describing the latest larger quake, a magnitude 3.6, that occurred around 11:30 p.m. Wednesday. It's the third quake above a magnitude 3 to hit over the last week.

"We're getting the full brunt of it here," says Ken Dewey, sitting in the Sweet & Smokey Diner.

Dewey's house is high above Sinclair Inlet, but only about 15 feet drop off to the water below. The Inlet is part of Puget Sound that runs between Bremerton and Bainbridge Island.

"Like a big truck moving through," says Dewey. "I'm in bed and then the bed started moving and I thought, 'Here we go!'."

The big concern for many here is that these 3.0+ quakes are a sign of something worse. Something experts say is not true.

The swarm of earthquakes has been occurring between Bremerton and the south end of Bainbridge Island.

"It's a livelier swarm than we've seen around here for a year or so," says John Vidale. He's a UW professor and runs the Pacific Northwest Seismic Network. "These earthquakes are not unusual around the Puget Sound."

Vidale says there are several theories on the reason behind these recent swarms of earthquakes in the waters off Bremerton.

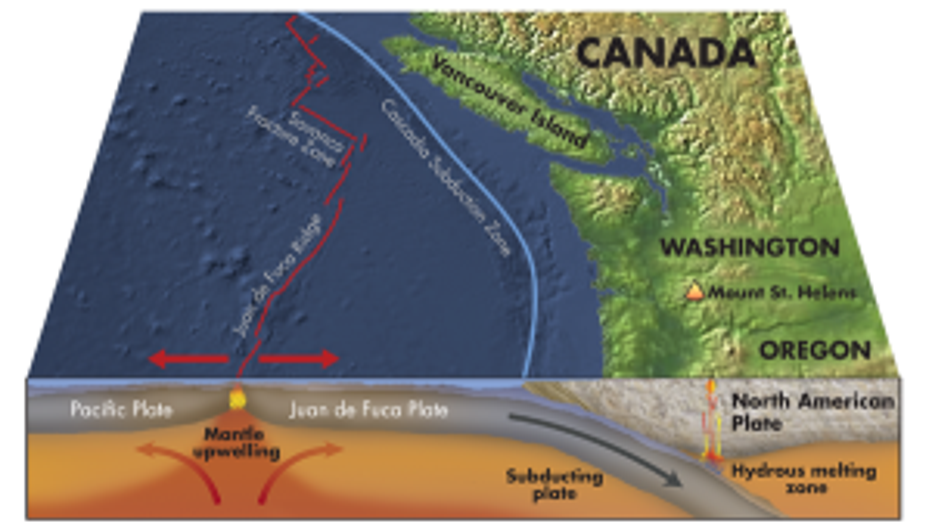

He says the source of the swarms could be from the ocean floor from far off-shore being dragged down underneath Western Washington. It's a plate tectonic boundary called the Cascadia Subduction Zone. The Juan de Fuca is diving underneath the North American plate. As the plate gets deep enough towards the hot core of the Earth, the water that's released from the rocks 15 miles down could be working its way back upwards. Vidale says the water is light and buoyant compared to the heavier rocks and mineral compounds which would sink.

Source: USGS

"So we think the water is pulsing through all these cracks in the ground and just flowing continuously. And sometimes the pressure builds up and pushes aside the fault and lets there be some activity."

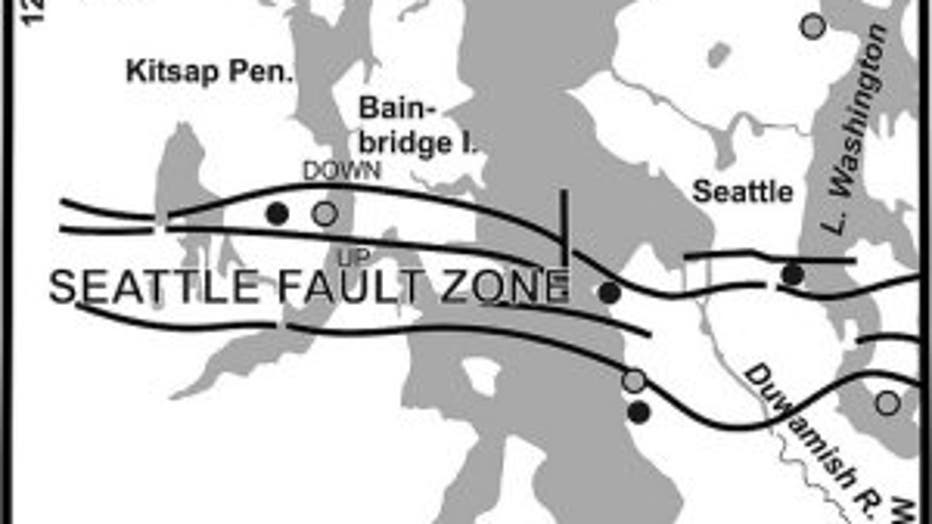

Vidale says in this instance the water could be considered much like a lubricant between moving factions at the west end of what's called the Seattle Fault. Much of what happens 15 miles under the surface of the Earth is still quite a bit of a mystery, says Vidale, "We look at a lot of different evidence, but it’s hard to have confidence the deeper we go in the earth, the less we know about where the faults are."

The Seattle Fault runs roughly west to east under Bremerton, Puget Sound, central Seattle, Bellevue and to the south end of Lake Sammamish.

"There's a whole system of faults in Western Washington," says Vidale, "and they're all moving in response to the tectonic plates."

Vidale says the Seattle Fault last ruptured violently about a thousand years ago with a 7.0+ earthquake and even resulted in a Puget Sound tsunami. But, Vidale says that fault line which only moves a few millimeters per year is not due to pop again any time soon. He

Source: Pacific NW Seismic Network

says the kinds of stresses in the Seattle Fault take many thousands of years to build. He says that's a much different geologic timeline than the Cascadia Subduction Zone fault off the Washington and Oregon coast that moves several inches every year.

The off-shore fault is widely considered to be the source of the next "Big One" for our region since evidence points very large quakes originating in that area every 300 or so years, the last one being in January of 1700.

"We have earthquakes here," says Vidale, "but that’s why we have mountains and the rivers and the beautiful dynamic topography. So it has costs and it has benefits."

Vidale says that because the scale on which earthquakes are measured is exponential instead of just linear, so according to Vidale, "the amount of pressure relieved is tiny. The magnitude scale is such that it would take an almost infinite number of tiny earthquakes to equal one big earthquake."

The reality of living in a geologically active area is apparent to both Ken Dewey and Don Ward -- both lifelong residents of the Bremerton area. Dewey says he goes down to the beach below his house and checks the cliff he lives on for signs of collapse after each larger quake, taking it all in stride.

"I was in the Marines so that helps."

For Ward at the salon, the says he understands our natural beauty is caused by natural processes like earthquakes.

"It's so beautiful here, I wouldn't want to live anywhere else."