Where's MY snow!? An easy guide to NW winter weather patterns

SEATTLE -- Nearly a foot of fresh powder in places blankets Portland, Oregon. And with winter wonderland pictures on social media of sledding kids and adults trekking to work on cross-country skis -- many people around Puget Sound are wondering "What gives!?"

Accumulating snow down to sea level is a rare occurrence, happening only every few winters for most of us in the lowlands of the Pacific Northwest. But some places just seem to be blessed/cursed with more snow than others. The answer is both simple and complicated. Let's walk you through the factors that go into why you're at work and others are enjoying a snow day.

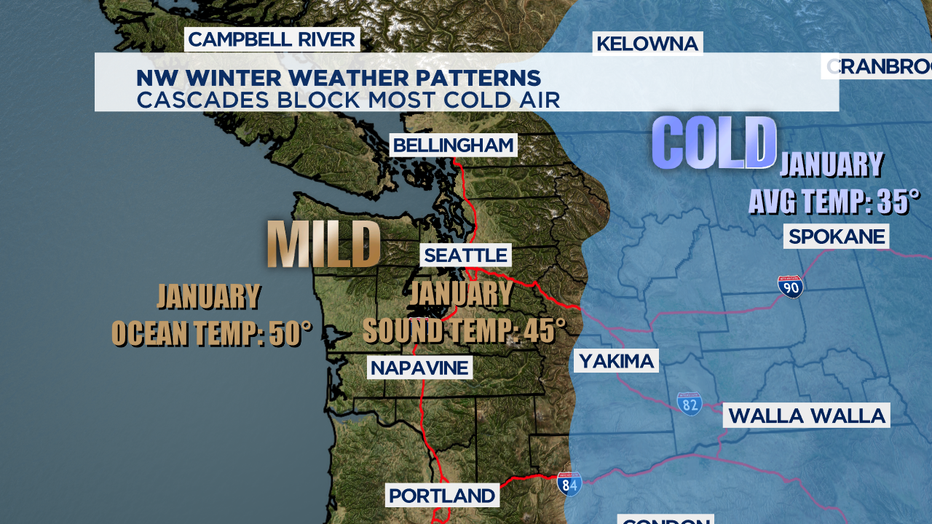

The easy answer first: the reason you don't have snow is that it's not cold enough most of the time. Now, let's dig a little deeper. Not all of the Pacific NW has the same climate patterns. East of the Cascades is what's known as a continental climate. It's cold and dry. The average January high temperature in Spokane is 35 degrees, that's very close to freezing already. West of the Cascades is what's known as a maritime (marine) climate. It's pretty mild over here. Even in January, the Pacific Ocean is about 50 degrees. Puget Sound's average January temperature is 45 degrees. And water holds heat better than land does, so it will warm the air above it. It shouldn't come as a huge surprise then, that the average January high temperature at SeaTac is 47.

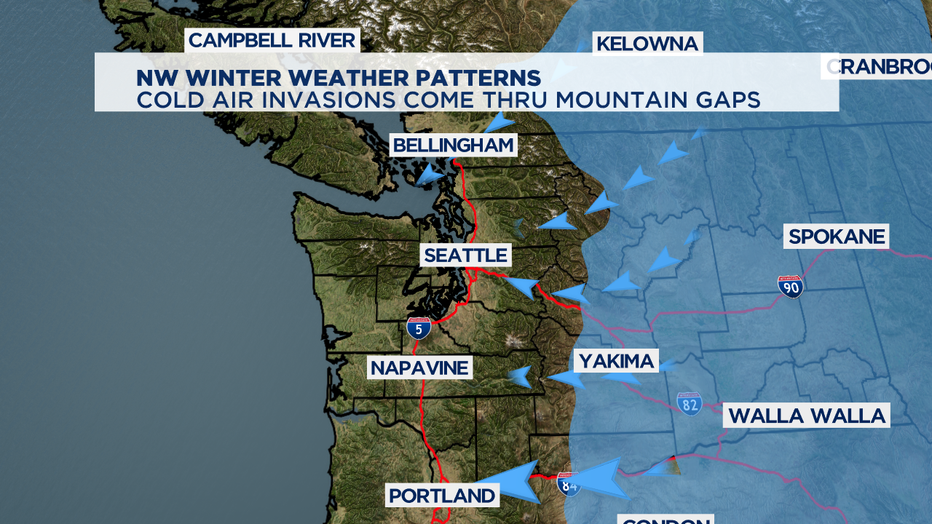

But, this isn't the case all the time. The cold air from the east can invade the west. It's been doing it a lot this winter. Cold air comes at Western Washington and Western Oregon through mountain gaps. The prevailing wind pattern happens to be from the N/NE when this happens. And while the Fraser River Valley in British Columbia is oriented this way, and the influence on the Bellingham area is pretty substantial. Closer to Seattle, Snoqualmie Pass is oriented towards the SE, so the influence on the Emerald City is not quite as pronounced.

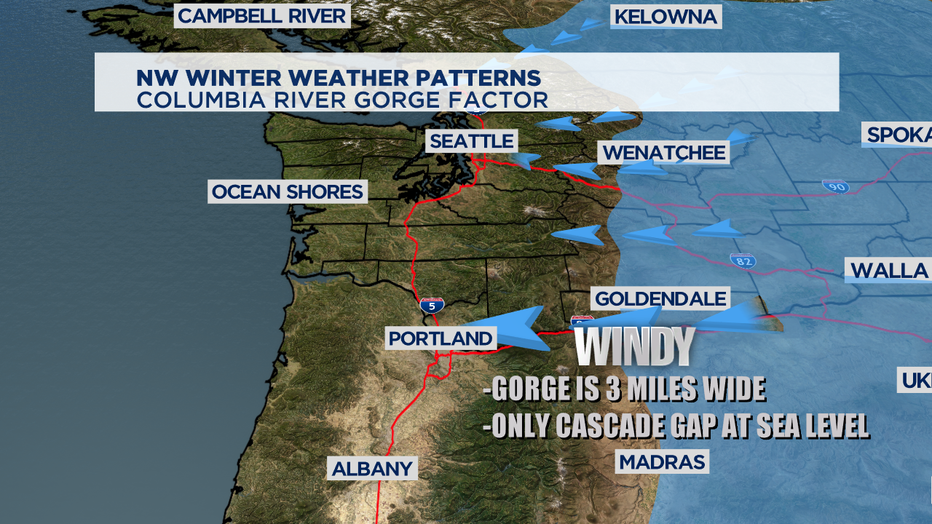

One of the biggest factors of all when it comes to invading cold air from the east is the Columbia River Gorge. Geologists say the evidence points to it being carved out about 12-17 million years ago. Ice dams breaking over and over near modern day Missoula, Montana broke allowed giant inland lakes to drain downhill -- blasting their way through the then growing Cascade Mountains. Known as the Missoula Floods, they scoured a channel for the Columbia River is about mile wide and the Gorge itself is about three miles wide on average. The Gorge is the only sea level gap in the whole Cascade Mountain chain and it drives a lot of cold air directly into the Portland Metro.

That cold air is dry and heavier than warmer air off of the Pacific Ocean. It sits in the lowlands of Western Oregon and Western Washington. Warmer air tries to take over, but often it is forced to go up and over the cold air. That's what's called an inversion-- when warm air sits on top of cold air. In areas around Puget Sound, the warmer ocean air can gain some territory back. The Chehalis Gap (between the Willapa Hills in SW Washington and the Olympic Mountains) and the Strait of Juan de Fuca allow the milder Pacific Ocean air to warm things back up for a lot of us. But, in some places--that cold air just gets stuck. The usual spots: Portland metro, SW Washington, Hood Canal, Willamette Valley. And those places on the front lines of where the cold air is invading from: Bellingham and the Columbia Gorge itself can get locked in the deep freeze for days after the rest of us have warmed up.

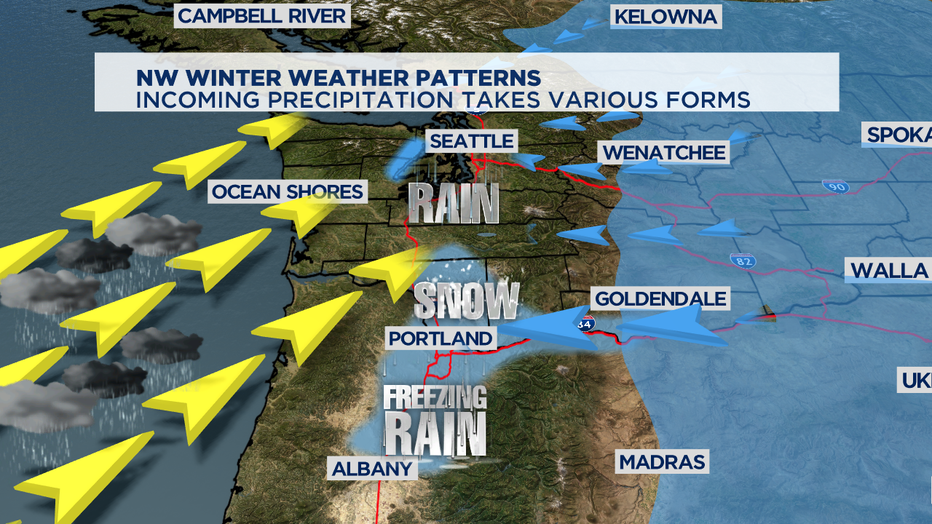

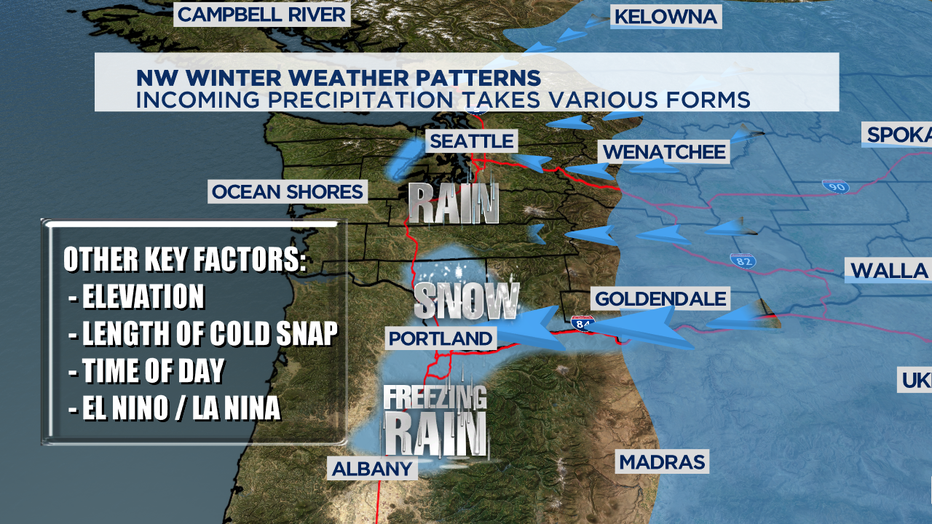

Usually these cold periods are sunny and dry around the region. But, eventually a storm heads our way. The come from out in the Pacific Ocean and when they arrive they deliver different kinds of precipitation to different places. Often the warmer air from the storm arriving is forced up and over the air mass that's parked in place along the I-5 corridor. Where the cold air mass is deep, the result is snow. Where the cold air mass is shallow, it delivers freezing rain. This is rain that falls as rain and freezes on contact with the frozen ground. Where the cold air mass isn't there at all, that precipitation falls as rain. Much of the time around Puget Sound it's a mix of rain and snow because the air mass is cold-- but not cold enough to get sticking snow.

Eventually, the warmer air will scour out the cold air stuck at the surface. That process sometimes can take many hours and in some extreme cases, several days. There are some additional factors that lead to whether you see snow in your backyard or along your commute. Elevation is a big one with our topography, often hills above 500 feet will see more snow than areas at sea level. The length of the cold snap matters too. If a cold blast lasts just a day, the ground will still retain a lot of heat. If an arctic invasion lasts a week, the ground will be frozen and primed for sticking snow. The time of day is important too. Our nights are long in the winter and temperatures plummet when the sun goes down that can mean precipitation that starts as rain in the afternoon can change over to snow as night falls. Often it ends up being a rain/snow mix that doesn't stick around for more than a few hours in Puget Sound lowlands.

And global weather patterns affect the Pacific Northwest too. Patterns like El Nino and its opposite weather pattern sister, La Nina, matter a lot. Those sea surface temperatures patterns down at the equator actually drive weather around the whole planet. Typically a La Nina winter, like we're currently seeing, is wetter than normal and colder than normal. So, the good news is if you're a snow lover just hoping for a winter wonderland. The weather patterns this season look like the chances are better than they've been in years for low elevation snow for everyone when the ingredients are mixed in the exact right proportions.